CME

Key Studies in Gastrointestinal Malignancies: Independent Conference Coverage of the ESMO 2025 Congress

Physicians: Maximum of 1.50 AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™

European Learners: 1.50 EBAC® CE Credit

Released: December 29, 2025

Expiration: June 28, 2026

Activity

MATTERHORN: Durvalumab + FLOT vs Placebo + FLOT in Resectable Gastric/GEJ Cancer

Samuel J. Klempner, MD, FASCO:

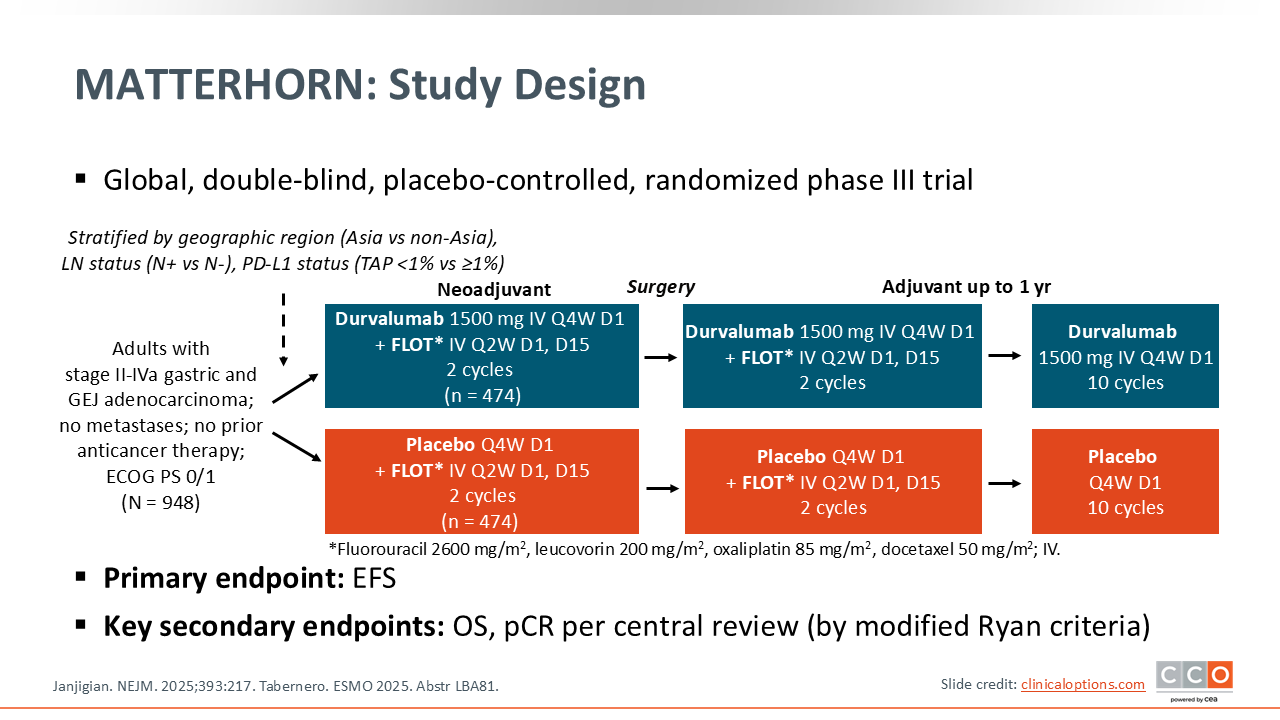

The phase III MATTERHORN trial asks a very important question: Does the addition of immunotherapy improve outcomes when added to standard perioperative chemotherapy, in this case the FLOT regimen, for patients with operable gastric or GEJ adenocarcinoma?1 It is a logical question, especially as the field of gastric and GEJ cancers has converged on perioperative therapies as the preferred standard approach in operable patients.

Key points to note about the study design, as well as the enrolled patient population, are that these are patients who were deemed appropriate for FLOT, which is the chemotherapy backbone used in both arms.1 This trial also enrolled patients from around the world, which is nice because it starts to harmonize and demonstrate that FLOT‑based chemotherapy is feasible around the globe. Finally, based on what we have learned from the use of immunotherapy in the metastatic setting, where we have seen varying degrees of benefit depending on the level of PD-L1 expression, patients were stratified by PD‑L1 expression, an important stratification factor.1

MATTERHORN: Final OS (ITT Population)

Samuel J. Klempner, MD, FASCO:

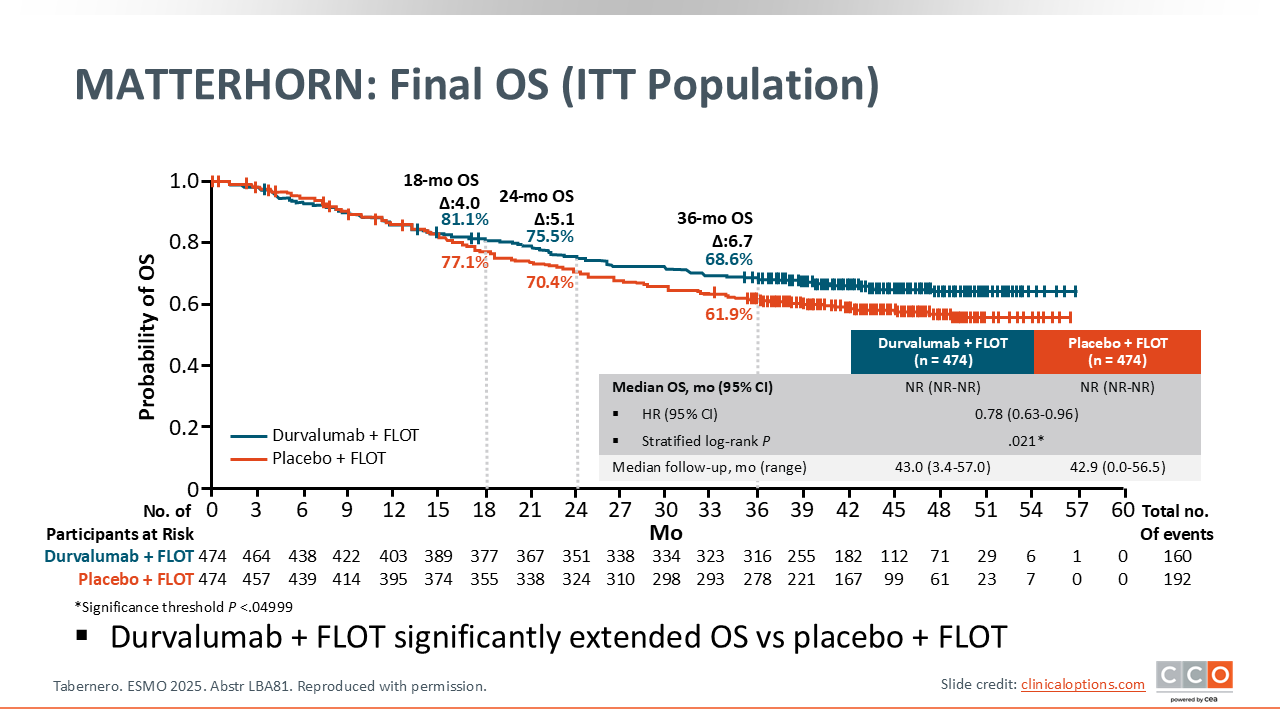

The primary endpoint of EFS was initially presented at the 2025 American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting and subsequently published.2,3 There was a statistically significant improvement in EFS with the addition of durvalumab to perioperative FLOT (2-year EFS rate: 67.4% vs 58.5% in the placebo group; HR 0.71 [95% CI: 0.58-0.86; P <.001]. However, the question remained whether the addition of durvalumab to FLOT could also improve OS. The OS results from MATTERHORN were subsequently presented at ESMO 2025 and demonstrated a significant improvement in OS, with an approximately 7% absolute improvement in 3-year OS rates with the addition of durvalumab, 68.6% vs 61.9% (HR: 0.78; 95% CI: 0.63-0.96; P = .021).1 Median OS was not reached in either arm. I do think it will be interesting to see the longer-term follow-up, but this trial, in my opinion, has now checked both boxes, improving EFS and OS.

MATTERHORN: Conclusions

Samuel J. Klempner, MD, FASCO:

The MATTERHORN trial asks a very clinical question, and therefore it has immediate clinical implications in terms of altering our standard approach. Prior to the MATTERHORN trial, we did not have phase III, level 1 evidence to support the addition of immunotherapy to perioperative chemotherapy for patients with gastric or GEJ cancer. Now we do, and it offers patients a significantly prolonged EFS and OS, which is a very welcome addition to the toolkit. Subsequently, the combination of durvalumab plus FLOT in the perioperative setting has been adopted by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines for patients with PD-L1 CPS ³1% or tumor area positivity (TAP) ³1% gastric, GEJ, or esophageal cancer4,5 and was approved by the FDA on November 25, 2025 for resectable gastric or GEJ adenocarcinoma independent of PD-L1 status.

As for the clinical implications, if a new patient with operable gastric, GEJ, or esophageal cancer presents to my clinic, durvalumab is being added to FLOT based on the results of the MATTERHORN trial. I do think the subgroup analyses are thought provoking and hypothesis generating, and there are some observations in the subgroups with regards to histologic type, clinical nodal status, PD‑L1 expression by TAP score, and anatomic tumor location that may influence discussions. However, in my own clinic, these will not impact exactly who I offer this combination to.

The safety and tolerability of FLOT is well-established from prior phase III trials, such as the FLOT‑4 study.6 We know that gastrointestinal toxicities, including nausea and diarrhea, as well as cytopenias are the primary toxicities with FLOT. In the MATTERHORN trial, for example, almost all patients completed the neoadjuvant component (96.6% and 94.5% completed durvaluamb and FLOT, respectively; 94.7% and 92.2% completed placebo and FLOT) and went to surgery (86.9% and 84.4% with durvalumab and placebo, respectively), and a large portion of patients were able to start the adjuvant component (75.9% and 52.3% started durvalumab and FLOT, respectively; 73.8% and 51.7% started placebo and FLOT).3 That tells me that we are getting better at giving this chemotherapy regimen, but we still need to be attentive to dose reductions to support patients through the treatment. It does not appear that the addition of durvalumab alters the toxicity profile of FLOT. Of course, we know about the rare immune‑related adverse events (AEs), but overall, I would say the toxicity between the control and experimental arms were quite similar and in line with both prior chemoimmunotherapy trials and FLOT as a general chemotherapy triplet. Deploying FLOT around the world requires a bit of experience and close patient follow-up and discussions. After giving FLOT for many years, we've learned to be upfront with patients about expected toxicities and to be liberal with dose adjustments. Close discussions with our surgical colleagues are another important practical point, because the surgeons need to be involved early on to assess the patients’ candidacy for surgery. They should be kept abreast of any clinical updates that might impact surgical timing, and should postoperatively assess surgical recovery and ability to resume the adjuvant component of FLOT. In summary, practical tips for administering this regimen are to be liberal with dose adjustments and have early conversations with surgeons and close patient follow-up.

Zev A. Wainberg, MD:

The MATTERHORN trial is a positive phase III study for OS and confirms what we had previously seen with EFS—that EFS is a good surrogate for OS, which is reassuring for the field as well. I think the MATTERHORN data have been practice changing for a while now, but even more so now after confirming an OS benefit.

I agree that it is important to note that the chemotherapy portion is associated with some pretty significant toxicity and may not be appropriate for all patients. Modifications to the chemotherapy are essential. This will continue to be a clinical judgment call, but I do not think the addition of durvalumab makes the chemotherapy less tolerable. In general, I think patients who are deemed to be good candidates for the FLOT regimen should have durvalumab added.

EDGE-Gastric Arm A1: Phase II Trial of Domvanalimab, Zimberelimab, and FOLFOX in Previously Untreated Advanced HER2-Negative GC/GEJC/EAC

Samuel J. Klempner, MD, FASCO:

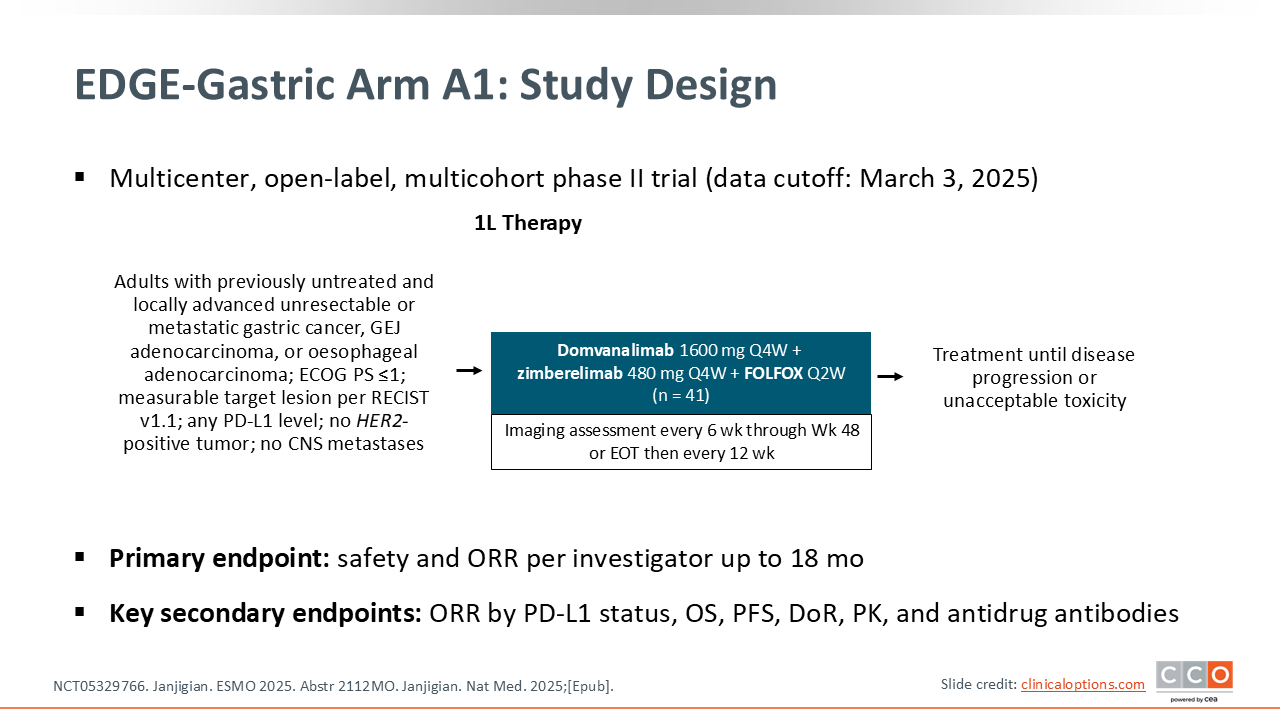

Continuing with the theme of immunotherapy and how to (1) expand the proportion of patients who might benefit from immunotherapy, and (2) extend the benefit beyond what we can achieve with current anti–PD‑1 therapies, updated data from the EDGE-Gastric Arm A1 were presented at ESMO 2025. This is the combination of standard first-line fluorouracil and oxaliplatin‑based chemotherapy with the investigational TIGIT inhibitor domvanalimab plus the PD‑1 inhibitor zimberelimab.7,8 The experimental question is, does adding an anti‑TIGIT antibody (domvanalimab) improve the activity, as assessed by both response rate and longer-term outcomes like PFS and OS in patients with previously untreated advanced gastric cancer, GEJ, or esophageal adenocarcinomas? The hypothesis is that dual‑checkpoint blockade may achieve better outcomes than what is seen with PD‑1 inhibitors plus chemotherapy, which is our standard combination in the first-line setting for metastatic gastric, GEJ, or esophageal cancer.

EDGE-Gastric Arm A1: Baseline Characteristics

Samuel J. Klempner, MD, FASCO:

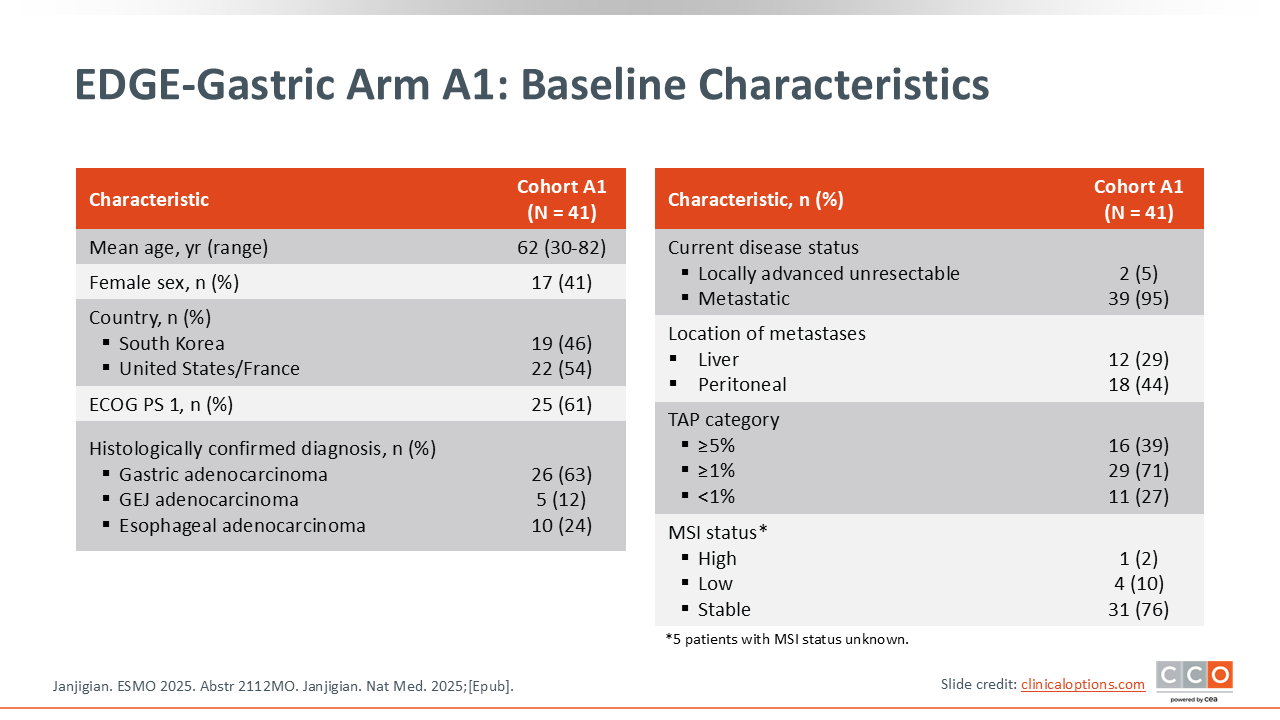

This is a single arm of a multicohort phase II trial that included 41 patients. Therefore, this needs to be interpreted with some degree of caution and may be impacted by potential patient selection, as there is no clear control group. Looking at the baseline characteristics, the population included is representative of real-world patients that I frequently see in clinic, and there is an expected distribution of PD‑L1 expression. Of note, in this trial PD-L1 is assessed by the TAP score, which can be thought of as relatively comparable to the CPS for PD‑L1.

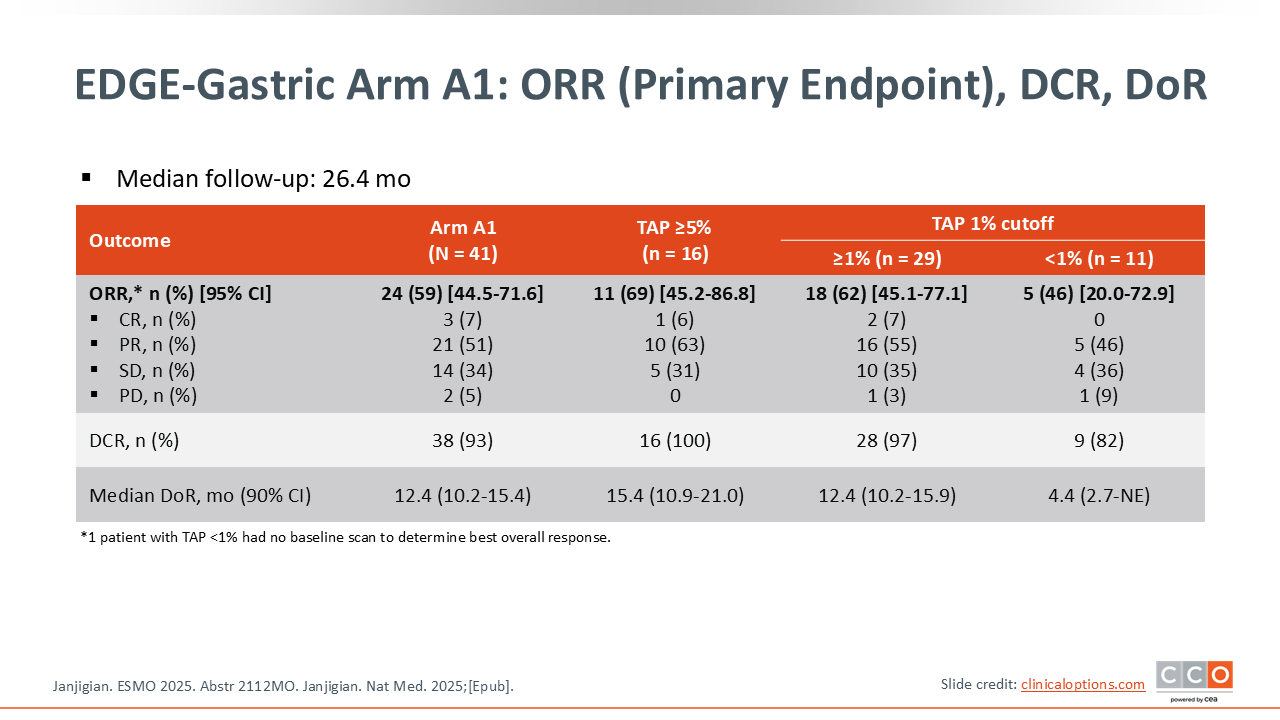

EDGE-Gastric Arm A1: ORR (Primary Endpoint), DCR, DoR

Samuel J. Klempner, MD, FASCO:

The coprimary endpoints were safety and investigator‑assessed ORR.7,8 In the associated publication, the waterfall plot depicting response rate showed expected patterns.8 One such pattern is that the biologic activity seems to correlate with tumor PD‑L1 expression level. So as you move from the patients with TAP <1%, to ³1% and then ³5%, you see the response rate improve. These are relatively small numbers, as there were less than 30 patients who were PD‑L1 positive. However, with an ORR of 59% overall, this is comparable if not numerically higher to what we typically see with chemotherapy plus a PD‑1 inhibitor.

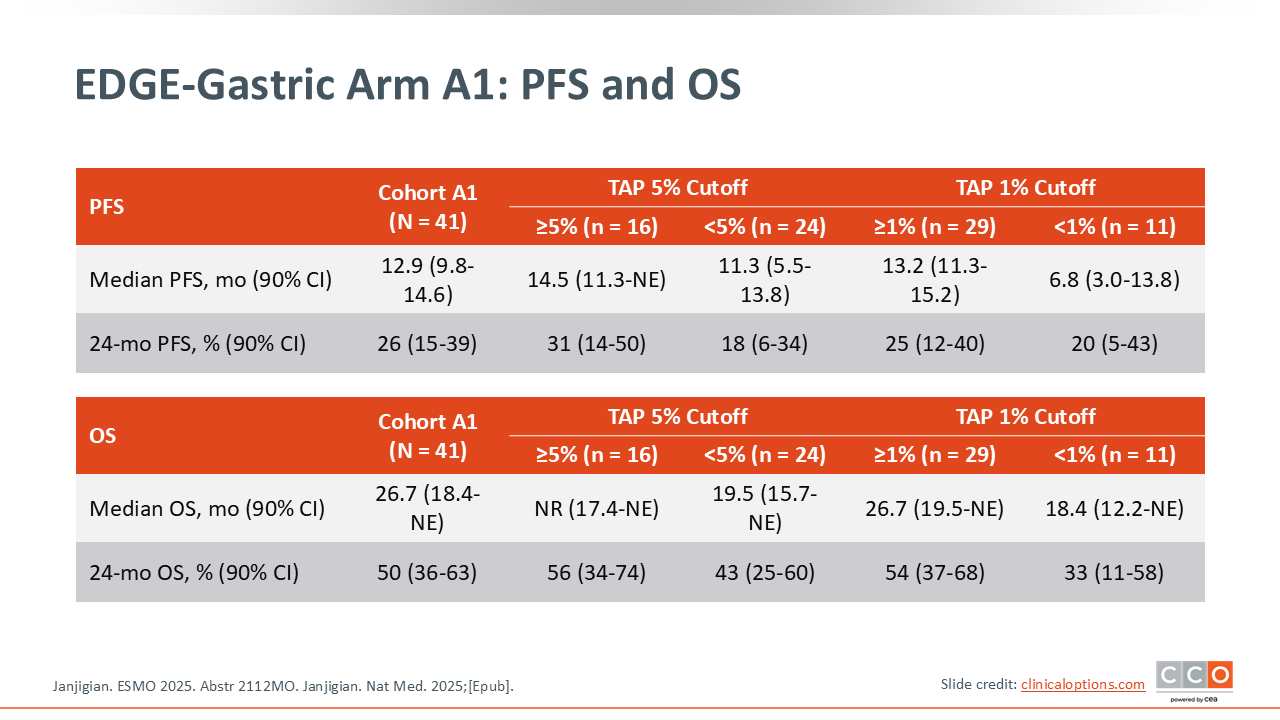

EDGE-Gastric Arm A1: PFS and OS

Samuel J. Klempner, MD, FASCO:

The survival outcomes in this update were quite interesting. In this phase II cohort, notable PFS and OS was observed. In the overall population, the median OS was 26.7 months, and the 2‑year survival rate was 50%.7,8 If you contextualize this compared to what we normally achieve with chemotherapy plus a PD‑1 inhibitor in phase III trials, the median OS is typically approximately 14-16 months.9,10

Unfortunately, according to a recent press release, these encouraging EDGE-Gastric findings were not validated in the STAR 221 (NCT05568095) global phase III trial, which evaluated the standard—FOLFOX and nivolumab—as the control and compared it against the experimental combination, as shown in the EDGE-Gastric Arm A1—FOLFOX and domvanalimab plus zimberelimab. The primary endpoint of improved OS with the experimental regimen compared with FOLFOX plus nivolumab was not met. We await presentation of the results; however, both the EDGE-Gastric and STAR-221 trials will be discontinued according to the sponsors.

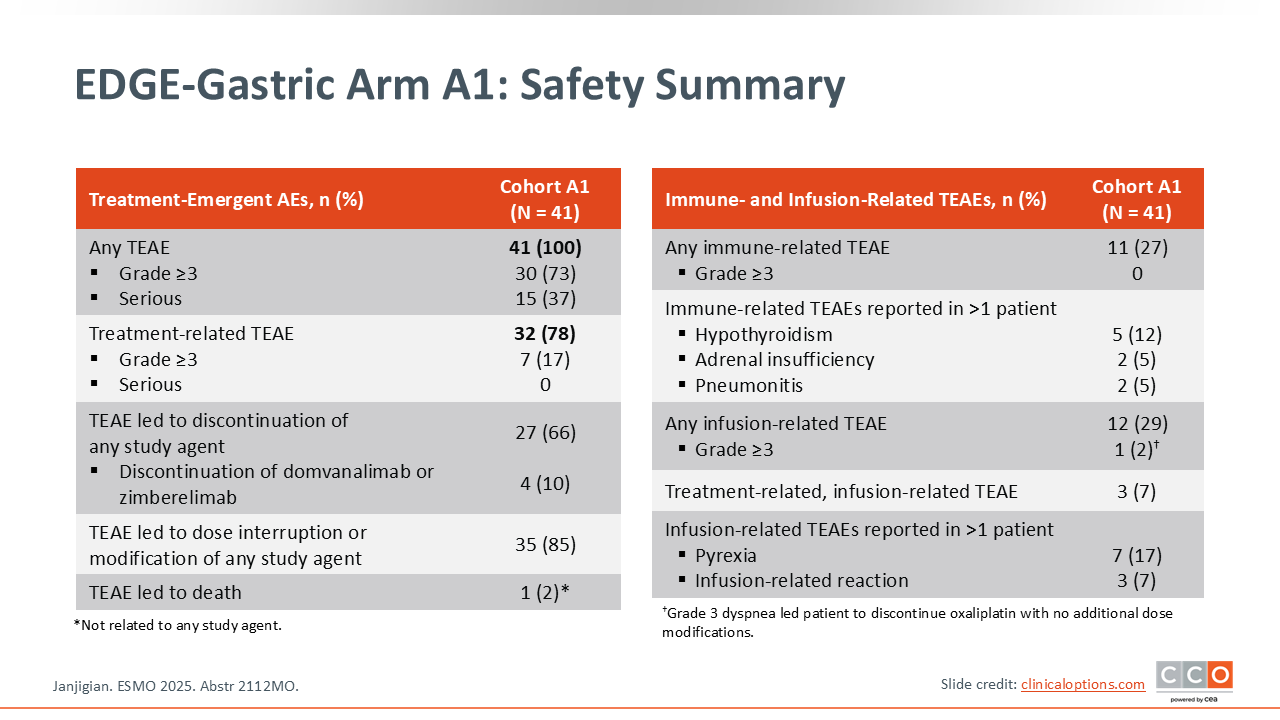

EDGE-Gastric Arm A1: Safety Summary

Samuel J. Klempner, MD, FASCO:

In terms of safety from this dual anti–TIGIT/PD‑1 inhibitor plus chemotherapy combination is that there does not appear to be a significant increase in toxicity when anti-TIGIT therapy is added on top of a PD‑1 inhibitor. Again, these are relatively small numbers.

EDGE-Gastric Arm A1: Conclusions

Samuel J. Klempner, MD, FASCO:

As noted above, the promising EDGE-Gastric results do not appear to have been validated in the STAR-221 phase III trial. We are now waiting for the presentation of this data. As the STAR-221 trial has upwards of 1000 patients enrolled, more patients per TAP group can be evaluated, as well as other biomarkers, to understand activity in specific populations and potential directions forward. I think the field is eager to have additional immunotherapy biomarkers and agents available. Anti-TIGIT therapy definitely has had mixed results to date across solid tumors and has yet to establish itself and agents like the PD-L1xTIGIT dual checkpoint bispecific rilvegostomig remain under investigation.

Zev A. Wainberg, MD:

I agree. It would seem that the STAR 221 phase III trial has answered the critical question of whether the regimen of FOLFOX and domvanalimab plus zimberelimab is better than standard of care nivolumab plus chemotherapy in terms of improving OS with the answer being no. I will be interested to see the data and any implications for moving forward. Some of the information we will be looking for will be whether any subgroups especially MSI-H or patients with very high PD-L1 levels derived any benefit from a dual checkpoint approach.

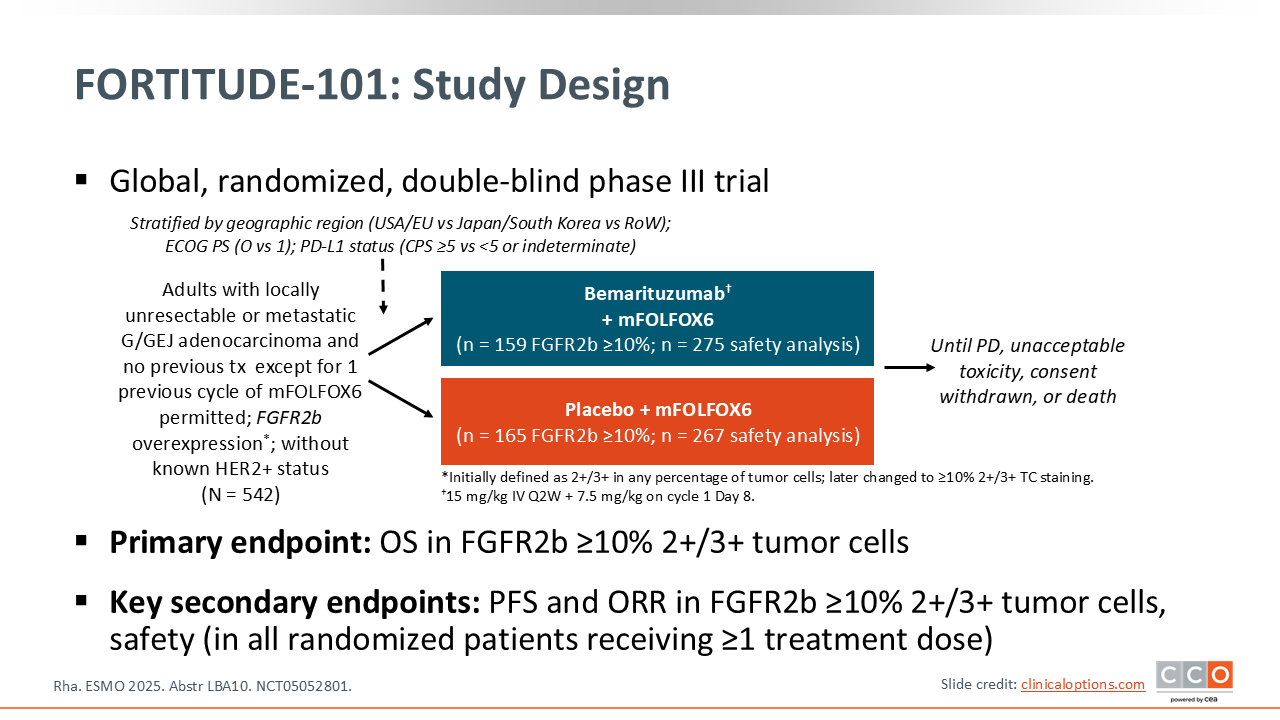

FORTITUDE-101: Bemarituzumab + mFOLFOX6 vs Placebo + mFOLFOX6 in Patients With Advanced/Metastatic FGFR2b-Overexpressing G/GEJ Cancer

Samuel J. Klempner, MD, FASCO:

The FORTITUDE‑101 trial asks a very straightforward question: In a biomarker-selected population, in this case an FGFR2b‑expressing tumor, does the anti‑FGFR2b antibody bemarituzumab improve survival when added to standard chemotherapy as first-line therapy for patients with gastric/GEJ adenocarcinoma?11 The background for this trial is that there was single-agent activity for bemarituzumab in FGFR2‑positive gastric/GEJ adenocarcinoma tumors as well as encouraging results from the randomized phase II FIGHT trial,12 and so there was a strong foundation for this trial.

There are a few points to highlight with regard to the study design. First, in the FIGHT trial, looking at those patients with FGFR2b positivity, the ones who had higher levels of expression benefitted the most.12 So the FORTITUDE‑101 trial was amended to adapt to this new biomarker threshold with FGFR2b overexpression defined as ≥10% with 2+/3+ tumor cell staining. That’s very important to understand as you go through the efficacy—that the efficacy in the target population is where the question is most relevant. There is a safety analysis that includes the patients enrolled before the amendment that changed the biomarker threshold.11

This trial was done in the first-line metastatic setting with patients who were HER2-negative. Immunotherapy was not a global standard when this trial was designed and it is important to note that there is no immunotherapy in either arm. You can argue that a most modern control arm would be chemotherapy plus immunotherapy as opposed to chemotherapy alone. That question is being asked in a separate phase III trial of bemarituzumab called FORTITUDE‑102 (NCT05111626), which is evaluating the addition of bemarituzumab to chemotherapy and nivolumab.

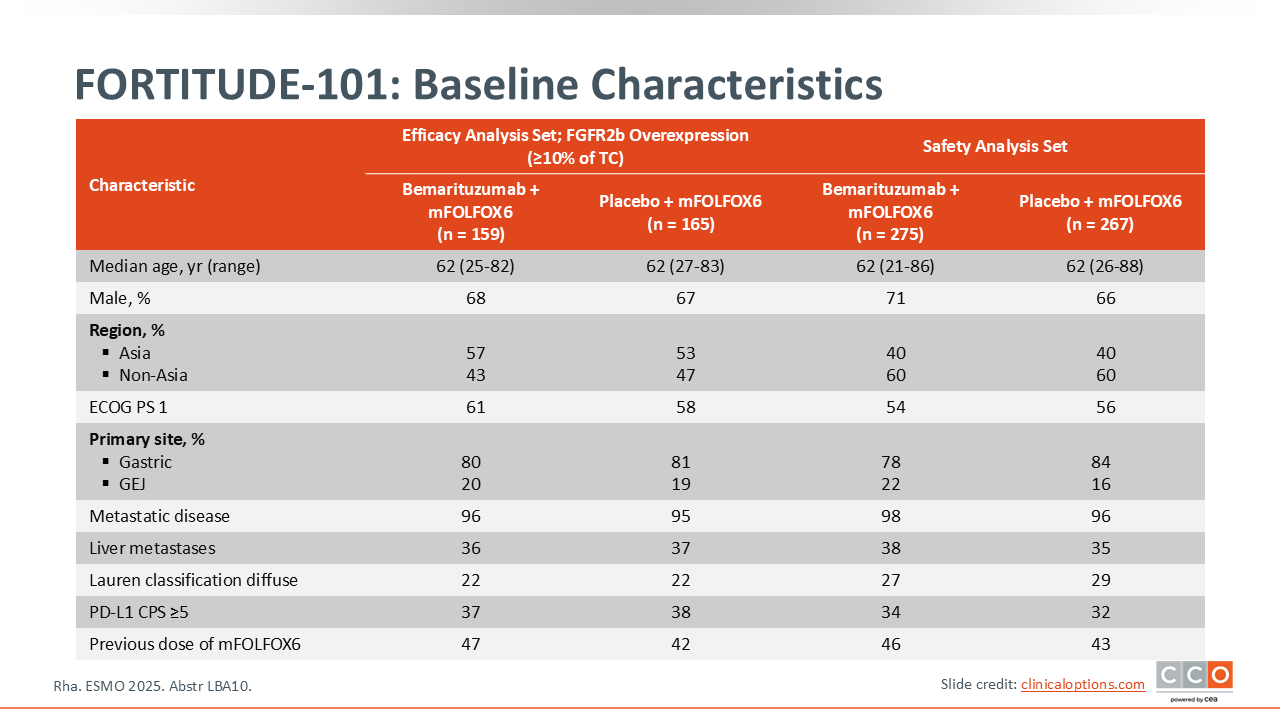

FORTITUDE-101: Baseline Characteristics

Samuel J. Klempner, MD, FASCO:

Overall, the patients enrolled in FORTITUDE-101 are representative of patients with gastric and GEJ cancer receiving treatment in the first-line setting. There are more patients with gastric cancer than GEJ, approximately one third of patients had liver metastases, and almost half of the study population received the 1 dose of FOLFOX chemotherapy that was allowed prior to the addition of the bemarituzumab.11 This single treatment cycle with FOLFOX was permitted while central biomarker testing was being completed. In order to not withhold therapy from these patients who may be symptomatic, they were allowed to get 1 cycle of FOLFOX at the discretion of the investigator. In summary, this appears to be a typical frontline patient population with gastric or GEJ cancers.

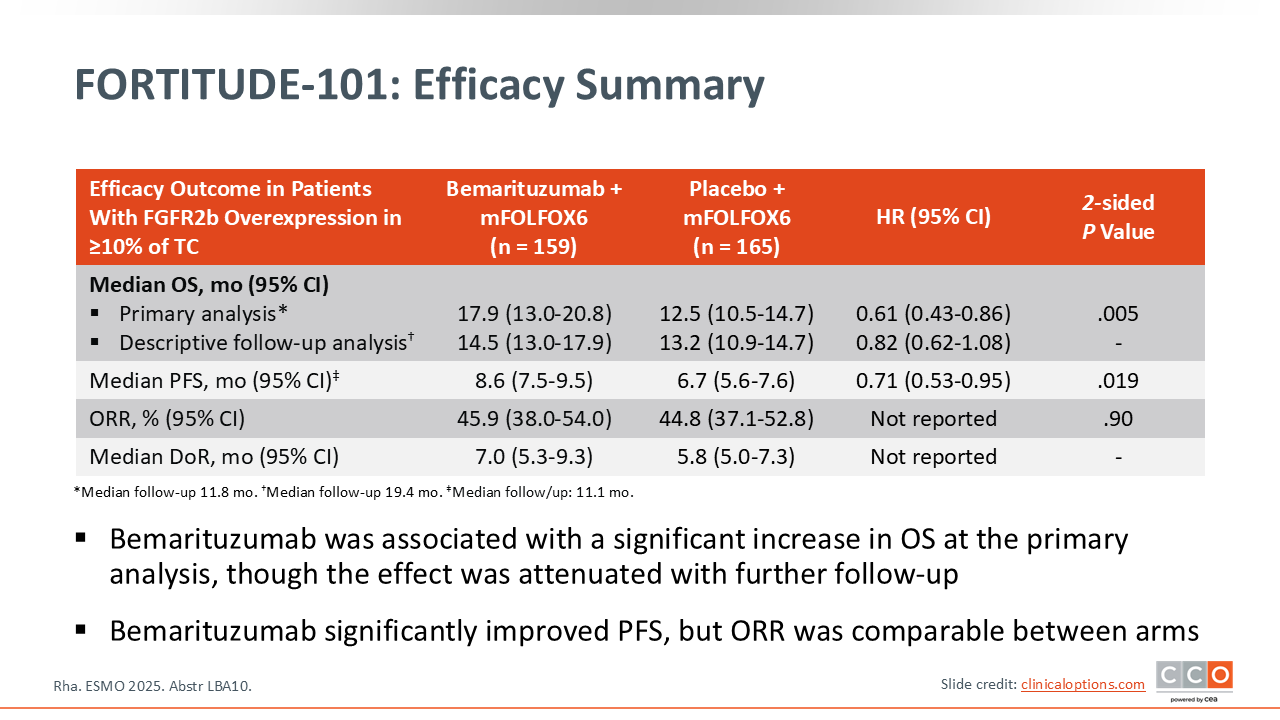

FORTITUDE-101: Efficacy Summary

Samuel J. Klempner, MD, FASCO:

Looking at efficacy, the primary endpoint was OS in the population with FGFR2b ≥10% 2+/3+ tumor cells.11 In this biomarker-selected population, there was a statistically significant improvement in OS at the primary analysis, with a hazard ratio of 0.61 (95% CI: 0.43-0.86) and a strongly significant P value of .005. This was promising. Of note, with this event‑driven analysis a significant difference was observed with a median follow-up of less than 1 year (11.8 months) on the trial.

However, with longer-term follow-up (median 19.4 months) in a descriptive analysis, an interesting observation occurred: the survival curves came closer together, starting around Months 10-14. The median OS with longer follow-up is now slightly over a month different between the experimental and control arms (14.5 vs 13.2 months). The hazard ratio, which was 0.61 at the time of the primary analysis, now has become 0.82. Again, this is a descriptive analysis with longer-term follow-up, so there is not a P value. However, it is difficult to ignore this change from a clinical standpoint. Basically, with an additional 8 and a half months of follow-up we see this change. This is not something we've seen often in oncology trials and raised some concerns.

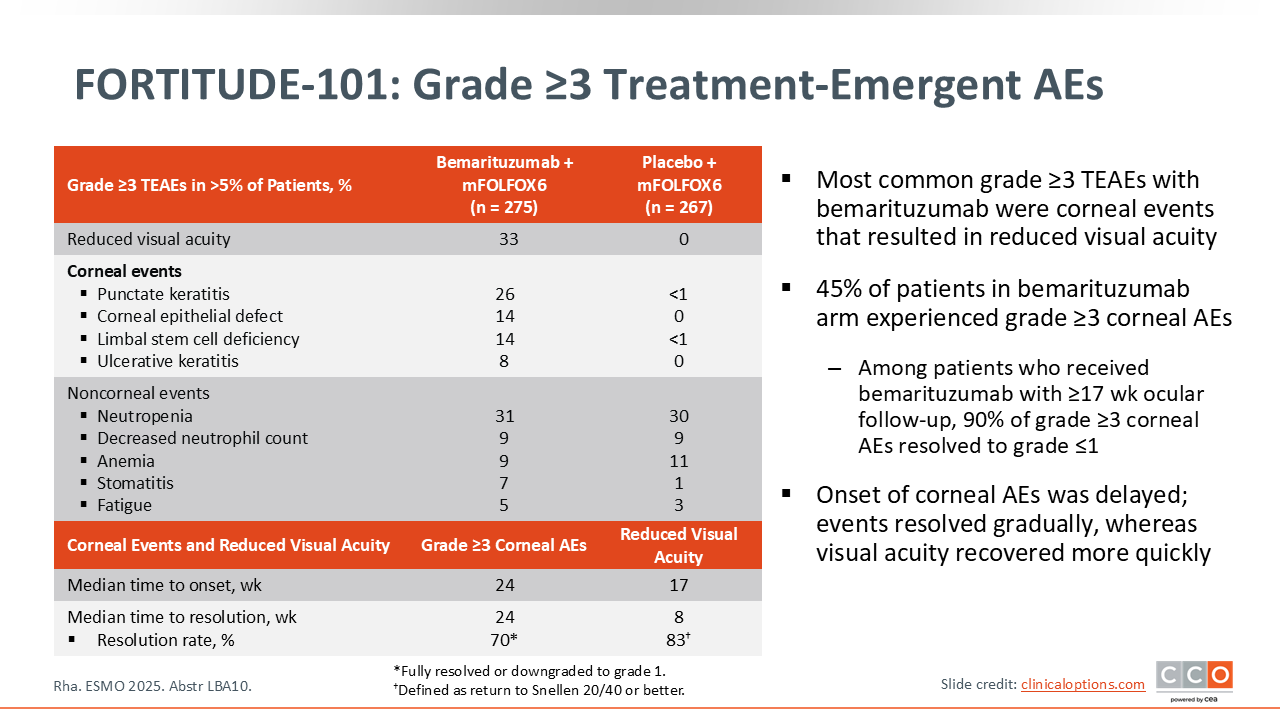

FORTITUDE-101: Grade ≥3 Treatment-Emergent AEs

Samuel J. Klempner, MD, FASCO:

Bemarituzumab has a known toxicity profile. The primary class‑specific toxicity is ocular side effects, which can manifest as anything ranging from dry eyes to decreases in visual acuity.11

The median time to onset of both the objective changes in ophthalmologic assessment as well as the more clinical changes in visual acuity is approximately 24 weeks. By that time, we already know if the patient is clinically responding because they've typically had a few scans and we also have a general sense of tolerability.

The FORTITUDE‑101 trial has taught us how to manage this ocular toxicity. Not to minimize the impact that this may have on a given patient but if you interrupt the drug, the time to resolution clinically is not that long—approximately 8 weeks.

FORTITUDE-101: Conclusions

Samuel J. Klempner, MD, FASCO:

Technically, FORTITUDE-101 is a positive phase III trial. Like the MATTERHORN trial, it was designed to have an opportunity to change the standard of care. However, looking at the longer-term follow-up and the median OS difference, especially when we put this in the context of the known side effects, it will not alter our standard of care. In addition, a recent press release indicated that the FORTITUDE-102 trial evaluating bemarituzumab plus chemotherapy and nivolumab in patients with first-line gastric cancer was stopped for inadequate efficacy. We are waiting to see this data to understand the implications. We may learn something from analysis of both the FORTITUDE 101 and FORTITUDE-102 trials about which patients, if any, may obtain benefit from bemarituzumab. I anticipate that there are a lot of analyses that will be done from these trials to better inform about this biomarker and patient selection and perhaps that will aid future studies..

Zev A. Wainberg, MD:

I think that the FORTITUDE-101 trial is an exceptionally confusing data set. The initial results were positive. Then, when patients were followed for a longer time period, a reduction in benefit was seen. And now hearing that the FORTITUDE-102 trial did not meet its primary endpoint. We’ll have to wait to see those data to see if there is a future with bemarituzumab even for patients with higher FGFR2b amplification, which would be very few of our patients with gastric/GEJ adenocarcinomas, up to 5%. Until then, we cannot draw many conclusions. That being said, we are committed to sequencing as many of the tumors as we can so we can answer some critically important questions.

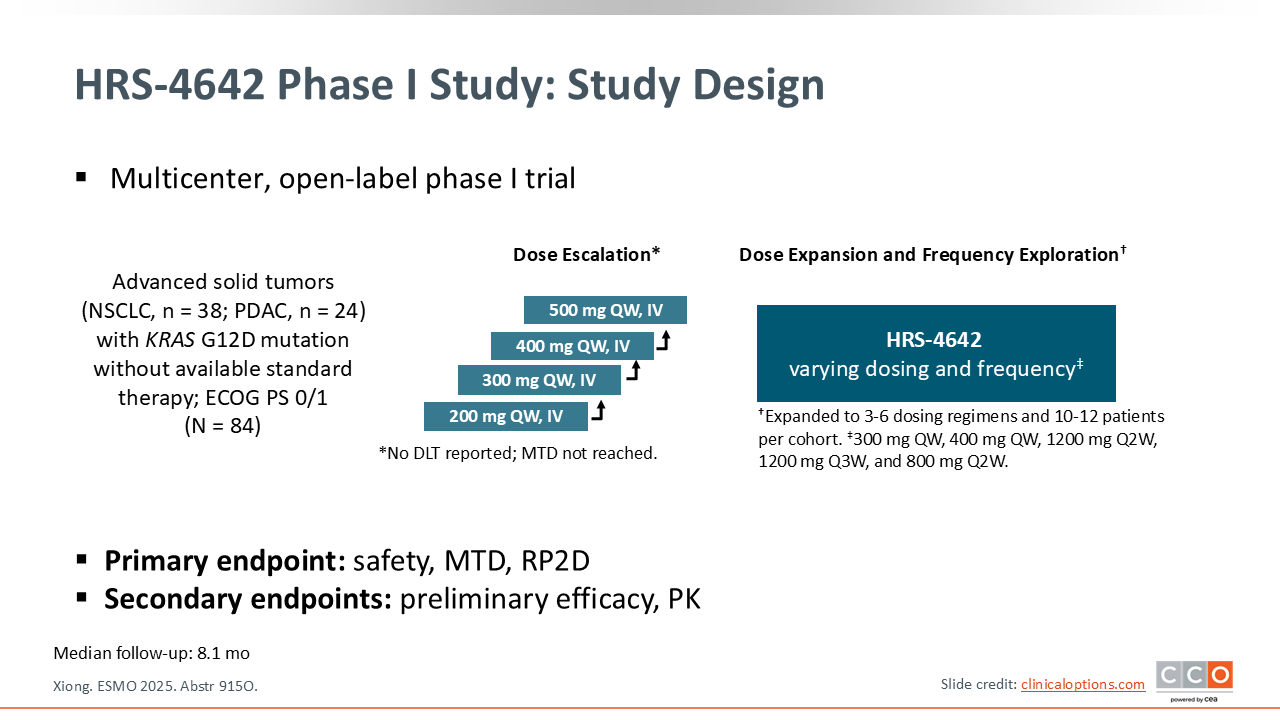

Phase I Trial of the KRAS G12D Inhibitor HRS-4642 in Previously Treated Advanced KRAS G12D–Mutant Solid Tumors Including PDAC

Zev A. Wainberg, MD:

As an introduction to the next 2 trials of investigational RAS-targeted therapies to be discussed, these emerging drugs fall into 3 main categories: (1) pan-RAS inhibitors, which block all RAS isoforms; (2) pan-KRAS inhibitors, which block all KRAS isoforms but spare HRAS and NRAS; and (3) isoform-specific inhibitors.13 The next 2 studies focus on isoform-specific KRAS G12D inhibitors in solid tumors, with a focus on pancreatic cancer.

In the first-in-human, phase I HRS-4642 trial, Dr Xiong and colleagues evaluated the impact of a novel KRAS G12D inhibitor in previously treated patients with KRAS G12D-mutated advanced solid tumors.14 This trial followed a typical dose escalation and expansion protocol.

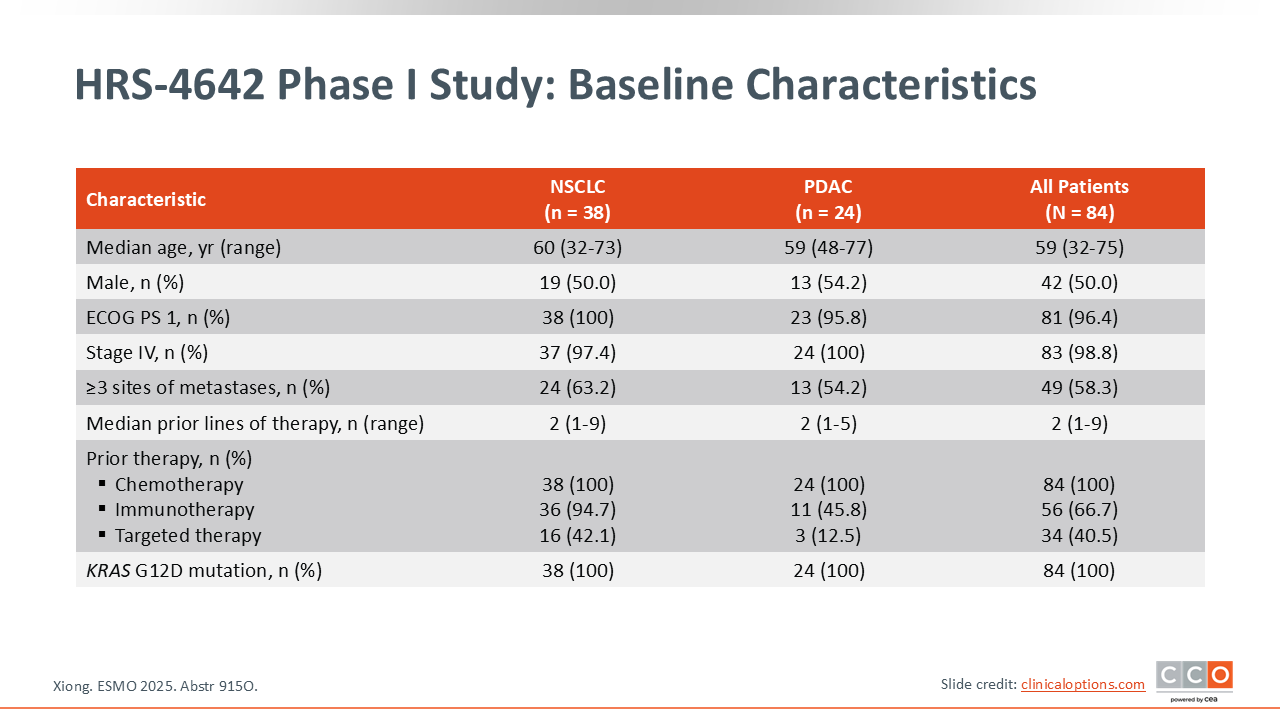

HRS-4642 Phase I Study: Baseline Characteristics

Zev A. Wainberg, MD:

The total enrollment was 84 patients, including 24 with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC).14

HRS-4642 Phase I Study: Safety

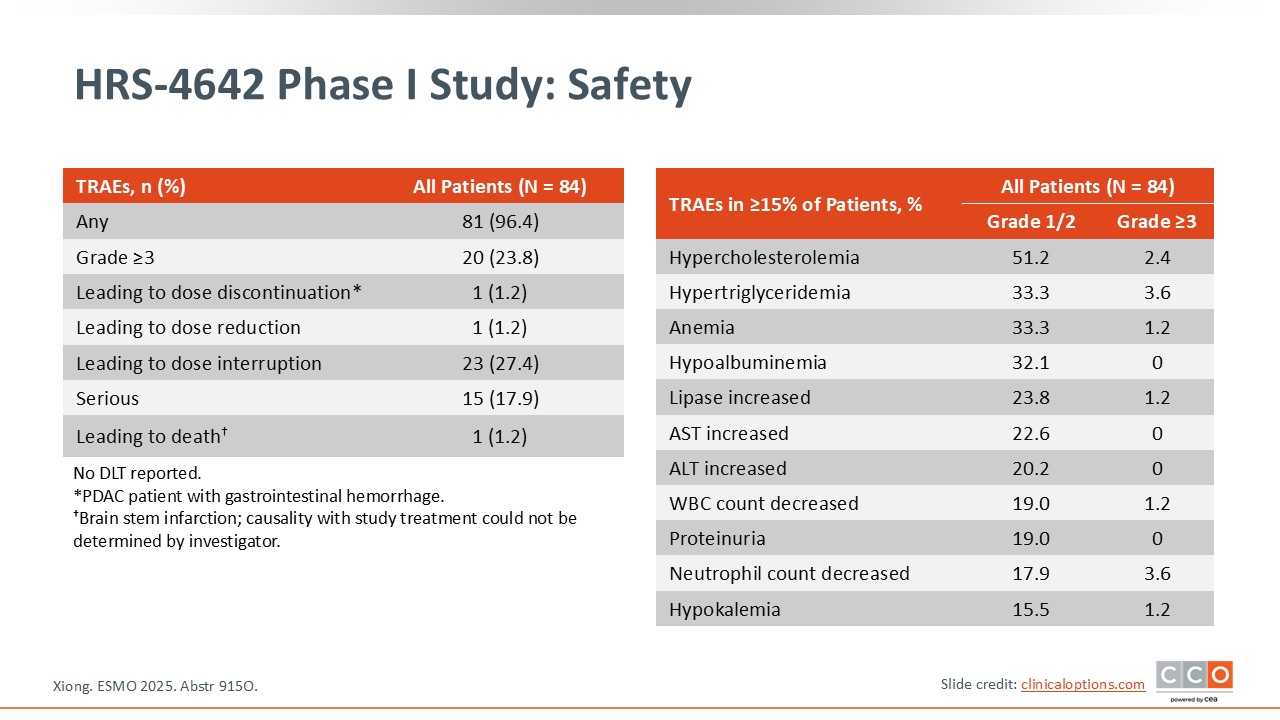

Zev A. Wainberg, MD:

In terms of safety, the drug appeared to be reasonably well tolerated. Almost one quarter (23.8%) of patients had grade ≥3 TEAEs, but almost none led to dose discontinuation.14 As with other G12D isoform-specific KRAS inhibitors, we are seeing patterns of fatigue and some mild liver function test abnormalities, but these are essentially very well-tolerated agents.

HRS-4642 Phase I Study: Activity

Zev A. Wainberg, MD:

If we focus in on the PDAC cohort, which is the subject of interest, they reached a dose of 1200 mg, which was declared the maximum tolerated dose.14 Among the total 24 patients enrolled in that cohort, the ORR was 20.8%, which included 5 patients with partial responses. The majority (58.3%) of patients had stable disease with only 4 showing disease progression. Although the confirmed ORR of 20.8% was modest, the disease control rate was quite high at 79.2%. Between the responses and disease control, this demonstrates an agent that patients were able to stay on.

The PDAC cohort had a median PFS of 4.1 months, which is lower than might have been expected. I think the data are a little immature at this time and we need to see how this drug performs in a larger cohort of patients. In addition, I think that we should look at this agent together with chemotherapy. In fact, there was a trial that combined HRS4642 with gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel in a phase Ib/II trial that was also presented at ESMO 2025.15 In that study, a much higher response rate was observed (63.3%), albeit in previously untreated patients with advanced solid tumors.15

HRS-4642: Conclusions

Zev A. Wainberg, MD:

I think that the future of HRS4642 may be in combination with chemotherapy. As a single agent, the ORR and PFS do not appear as good as previous results reported with other KRAS G12D inhibitors. Therefore, my expectation for the future development of this drug is in combination with chemotherapy.

Phase I Trial of the KRAS G12D Inhibitor INCB161734 in Previously Treated KRAS G12D–Mutant Advanced Solid Tumors

Zev A. Wainberg, MD:

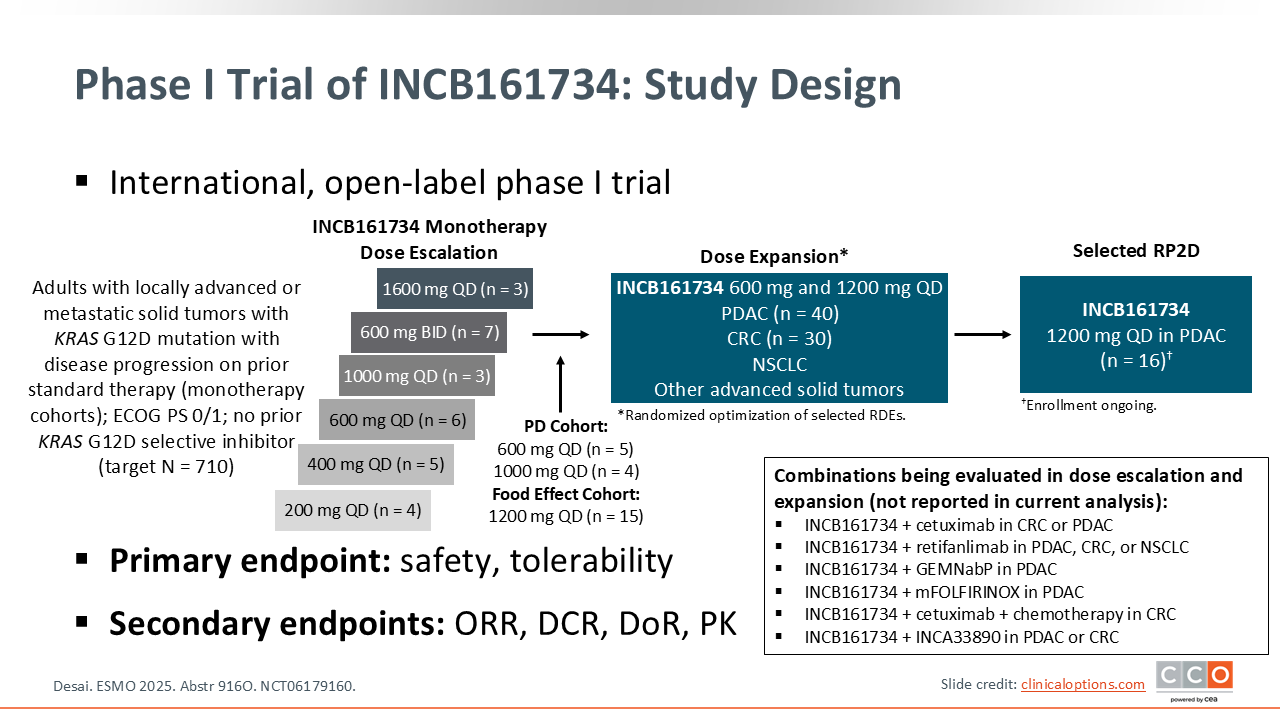

We also saw data with another KRAS G12D isoform-specific inhibitor that is very selective for G12D. This phase I trial included a series of dose escalation and expansion cohorts.16 The total data included 138 patients, with a PDAC cohort of 83 patients.

Phase I Trial of INCB161734: Most Common TRAEs

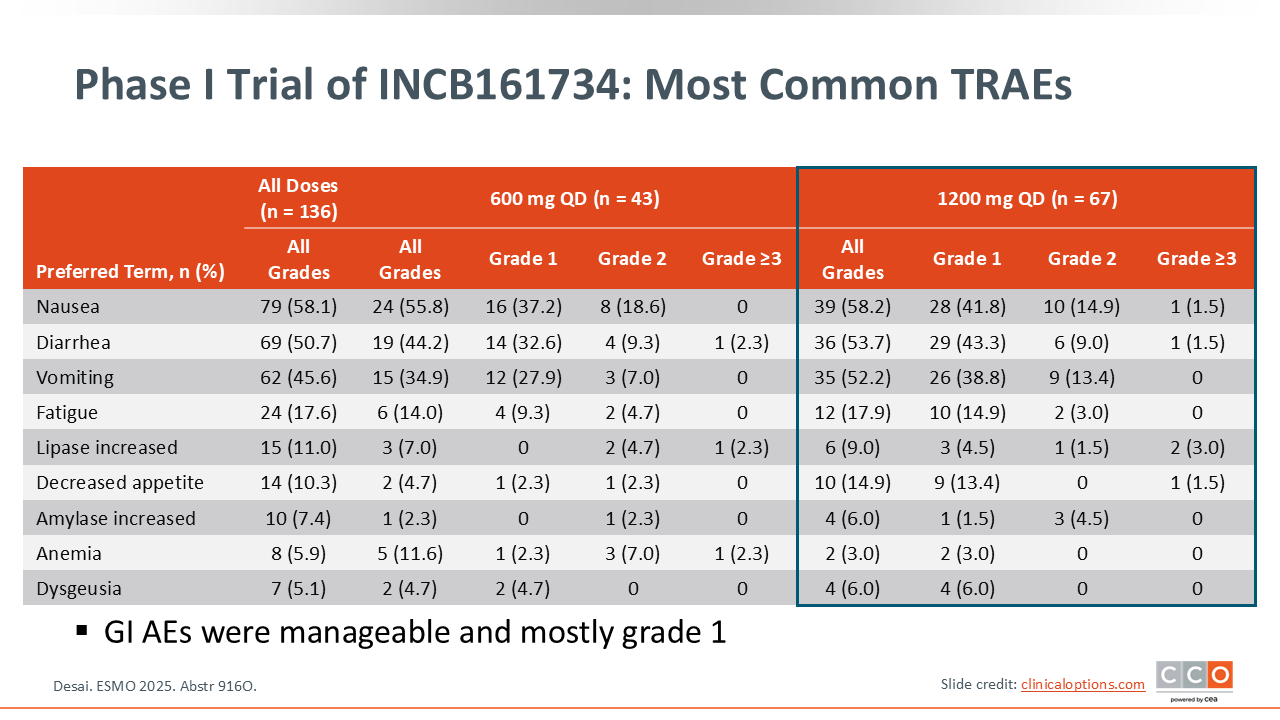

Zev A. Wainberg, MD:

The most common TRAE reported with this drug was gastrointestinal toxicity.16 At the recommended phase II dose of 1200 mg daily, nausea was the most common AE, occurring at any grade in 58.2% of patients. This may be ameliorated with antiemetics and by taking the drug in the evening, but gastrointestinal toxicity is notable with this agent.

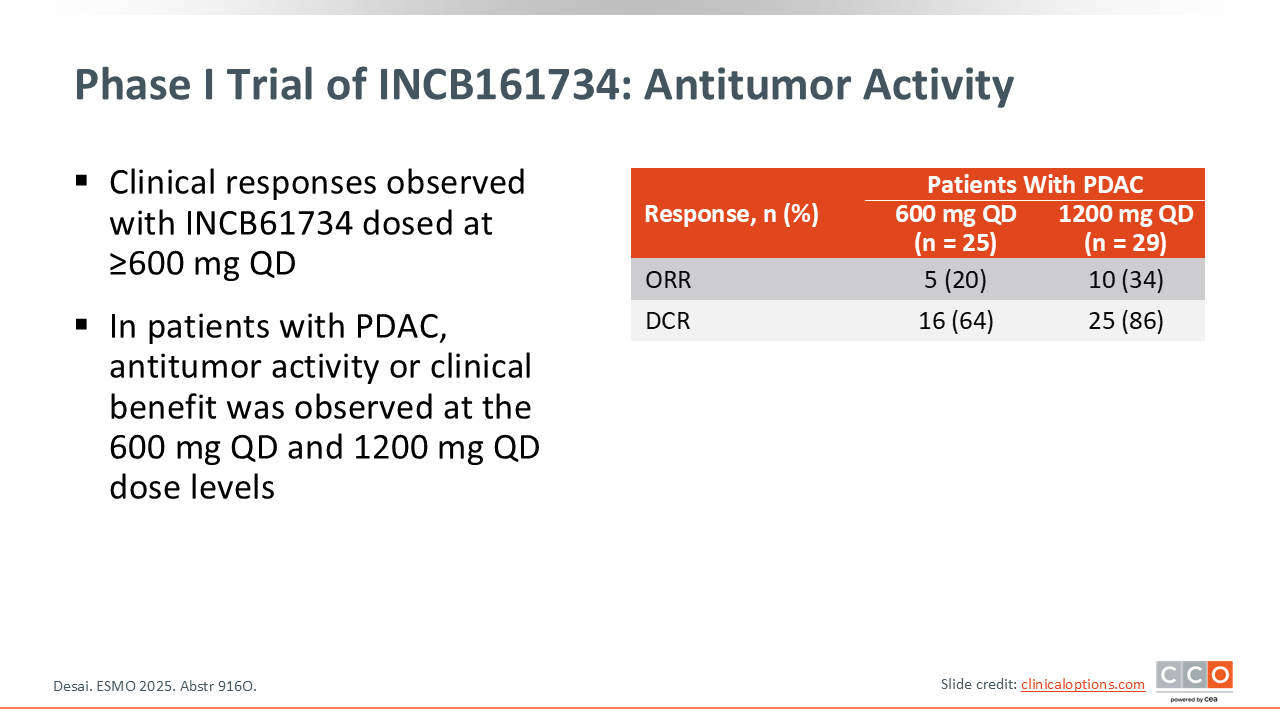

Phase I Trial of INCB161734: Antitumor Activity

Zev A. Wainberg, MD:

With the 1200 mg dose, there was a response rate of 34% among the 29 patients with PDAC. Of the 25 patients receiving 600 mg, the ORR was 20%.16 Survival data were not reported, as the data were too immature. This agent is also being evaluated in combination with chemotherapy. Overall, both KRAS G12D inhibitors are promising, and I anticipate they may have potential for patients with advanced pancreatic cancer in combination with chemotherapy.

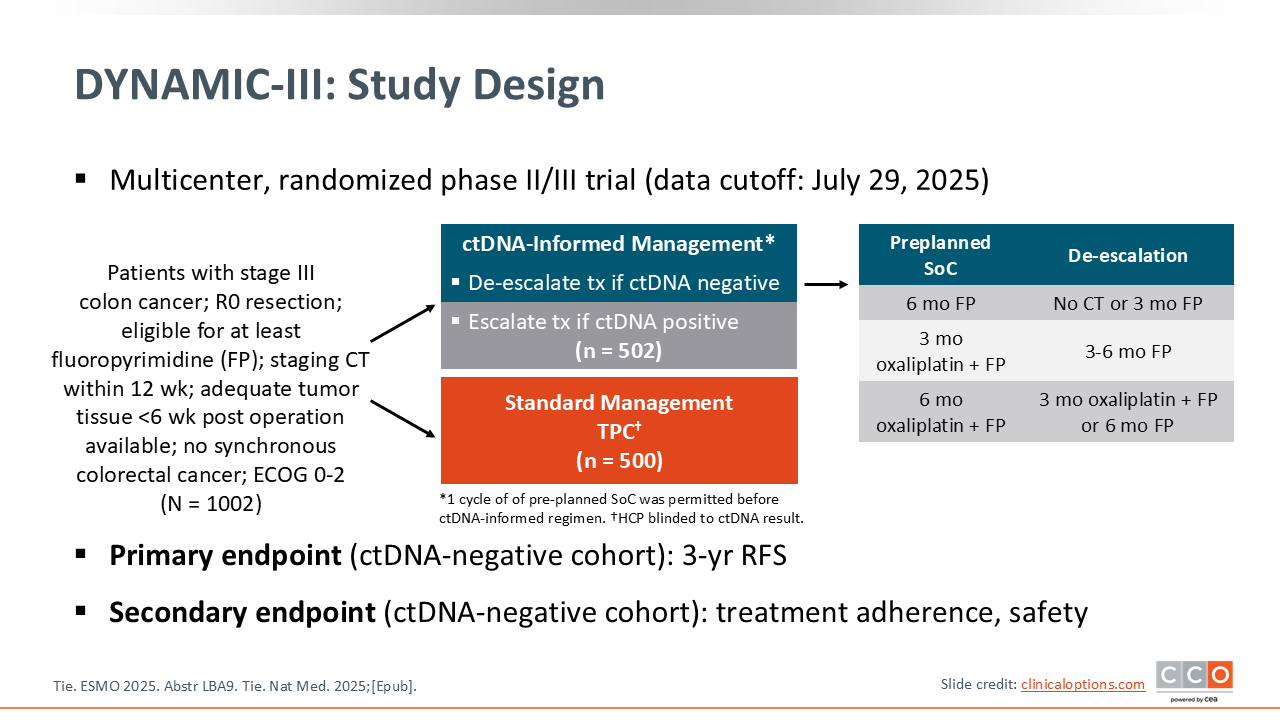

DYNAMIC-III: De-escalation of Adjuvant CT in the Postoperative ctDNA-Negative Cohort of Patients With Stage III Colon Cancer

Zev A. Wainberg, MD:

The long-awaited DYNAMIC-III study looked at de-escalation of therapy in patients with stage III colon cancer receiving adjuvant chemotherapy who tested negative for circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA).17 We have known for a number of years from trials in many tumor types that patients who have persistent ctDNA after curative intent therapy—whether its chemoradiation, surgery alone, or perioperative chemotherapy—generally have a much higher rate of recurrence and shorter survival. So it is a clear, independent prognostic variable. Similarly, in the metastatic setting, we have seen ctDNA kinetics over time be predictive of PFS and OS. Finally, the absolute amount of ctDNA in the blood may also be prognostic.

What has not been shown is whether acting on a ctDNA-positive or -negative result and changing the management accordingly would improve patient outcomes. That is what this study sought to do. They included patients who were ctDNA negative following surgery and randomized them to either the same chemotherapy as was originally planned or a ctDNA-informed management approach, which included de-escalated treatment options such as no chemotherapy, fluoropyrimidine alone, or a shorter duration of treatment. The question was whether the risk of recurrence would be impacted if adjuvant treatment was de-escalated based on ctDNA-negativity. In that background, the DYNAMIC‑III trial really sought to extend the role of ctDNA from the stage 2 population, where we had already seen data,18 into the setting of stage 3 colon cancer.

They enrolled a significant number of patients who had surgery, with a complete resection, and then were planned for adjuvant chemotherapy; overall 1002 patients were randomized on this study. The analysis included 353 patients who were ctDNA-negative and underwent informed de-escalation in adjuvant therapy and 349 who received standard management. The study was designed as a noninferiority trial, and that is really what the DYNAMIC‑III trial was testing. Basically, can we improve the 3-year recurrence free survival (RFS), and also evaluate the use of less chemotherapy without compromising outcomes in the ctDNA‑negative population?

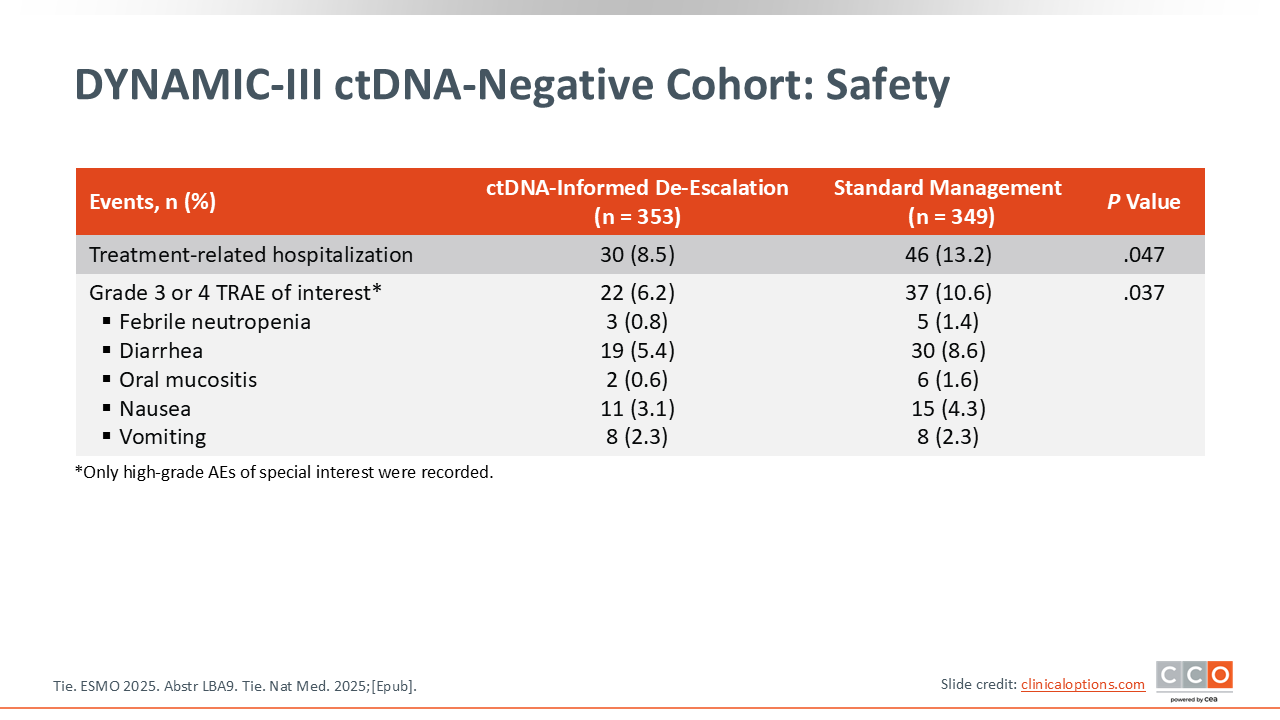

DYNAMIC-III ctDNA-Negative Cohort: Safety

Zev A. Wainberg, MD:

As expected, rates of grade 3 or higher febrile neutropenia, diarrhea, mucositis, nausea, and vomiting were lower in the patients who received less chemotherapy in the ctDNA-informed de-escalation arm.17

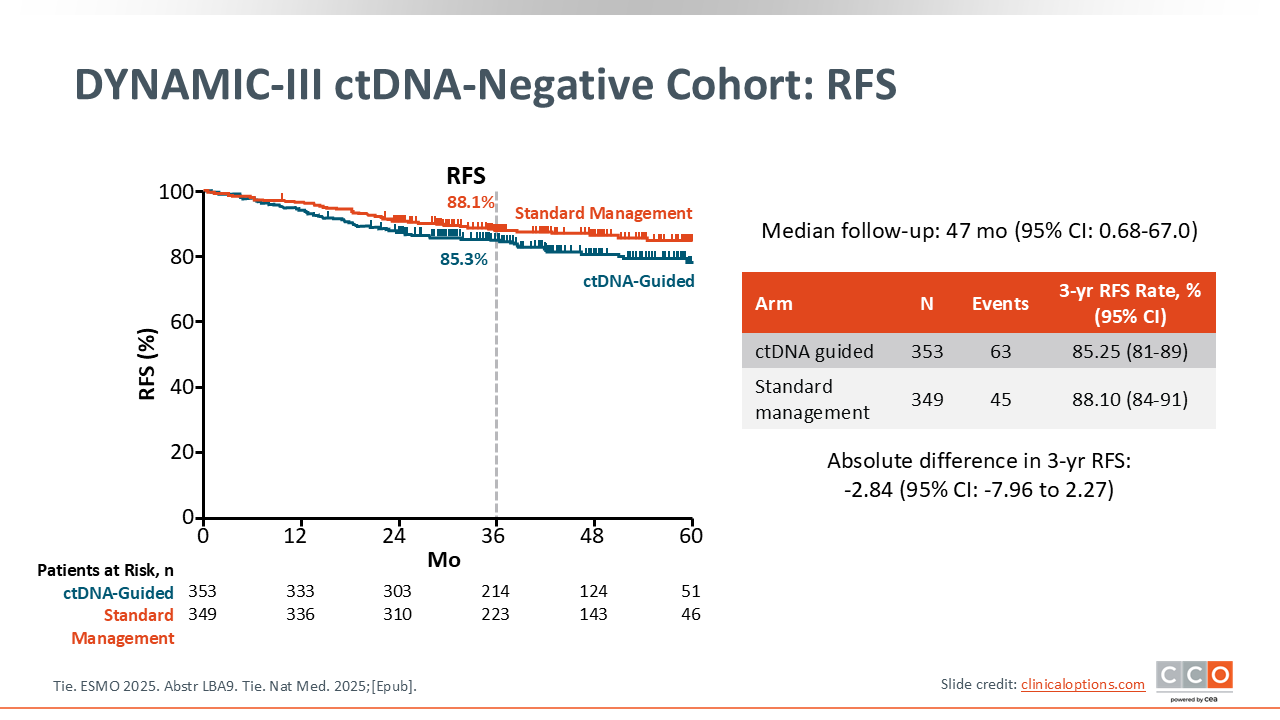

DYNAMIC-III ctDNA-Negative Cohort: RFS

Zev A. Wainberg, MD:

Unfortunately, after almost 4 years of follow-up, the de-escalation approach did not meet the criteria of noninferiority with the trial design allowing up to 7.5%, which was the lower bound of the noninferiority margin as what was considered acceptable.17

Samuel J. Klempner, MD, FASCO:

Noninferiority design and boundaries are always a topic for debate. Some healthcare professionals would argue that that is too wide a wide margin to consider clinically acceptable and others would say it is acceptable. Everyone has some varying thoughts on noninferiority design.

Technically this was a negative study, so they did not confirm noninferiority in terms of RFS for the use of a ctDNA de‑escalation strategy. So will it change practice? Probably not, in my own opinion. What can we learn from this trial? Certainly, we learned that it is feasible to do this. They were able to complete this strategy of surgery, ctDNA assessment, and use the result to inform the adjuvant therapy approach. So that is an accomplishment. It remains to be seen how patients feel about this approach. I think there will be a lot of important learnings from some of the additional tools built into this trial design, in terms of tolerance and toxicity. We already saw some of the rates of neuropathy, etc being lower. So there are some practical implications to using less chemotherapy, which we largely already knew. But technically, this is a negative trial.

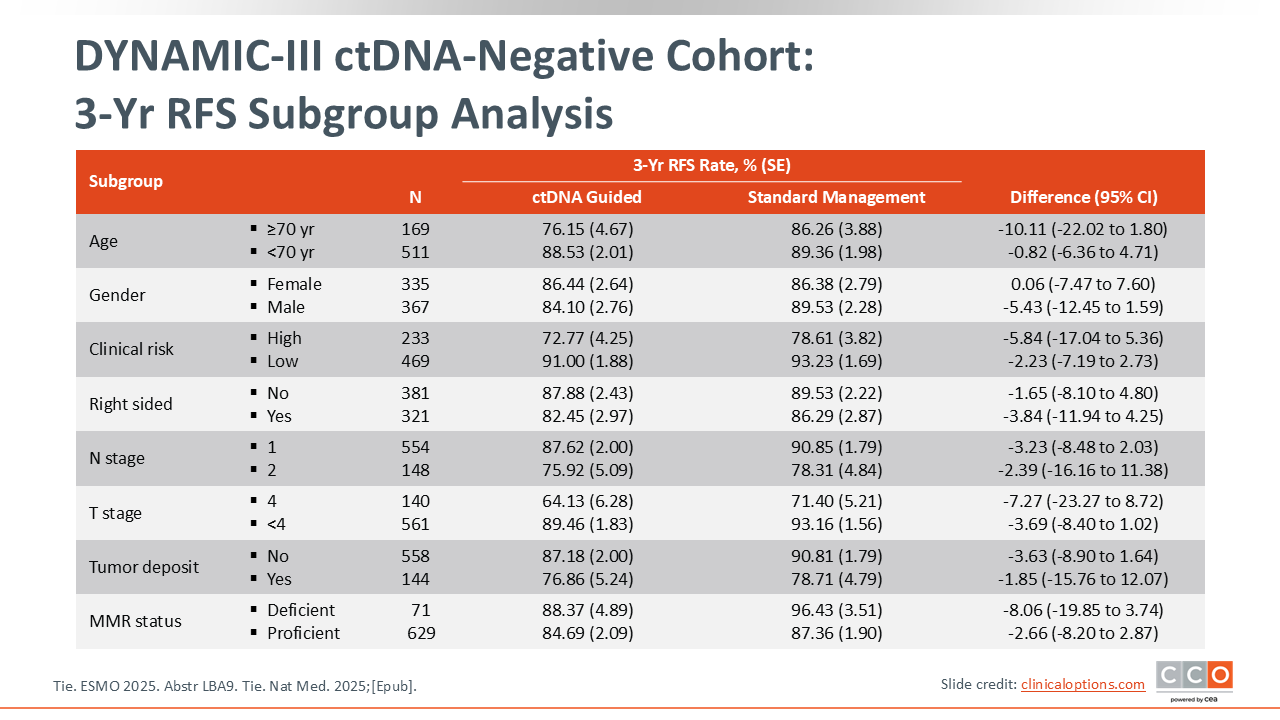

DYNAMIC-III ctDNA-Negative Cohort: 3-Yr RFS Subgroup Analysis

Zev A. Wainberg, MD:

Almost all of the subgroups favored the standard approach to treatment.17 This was particularly evident in the group of patients with higher risk features, including T4 tumors and N2 disease.

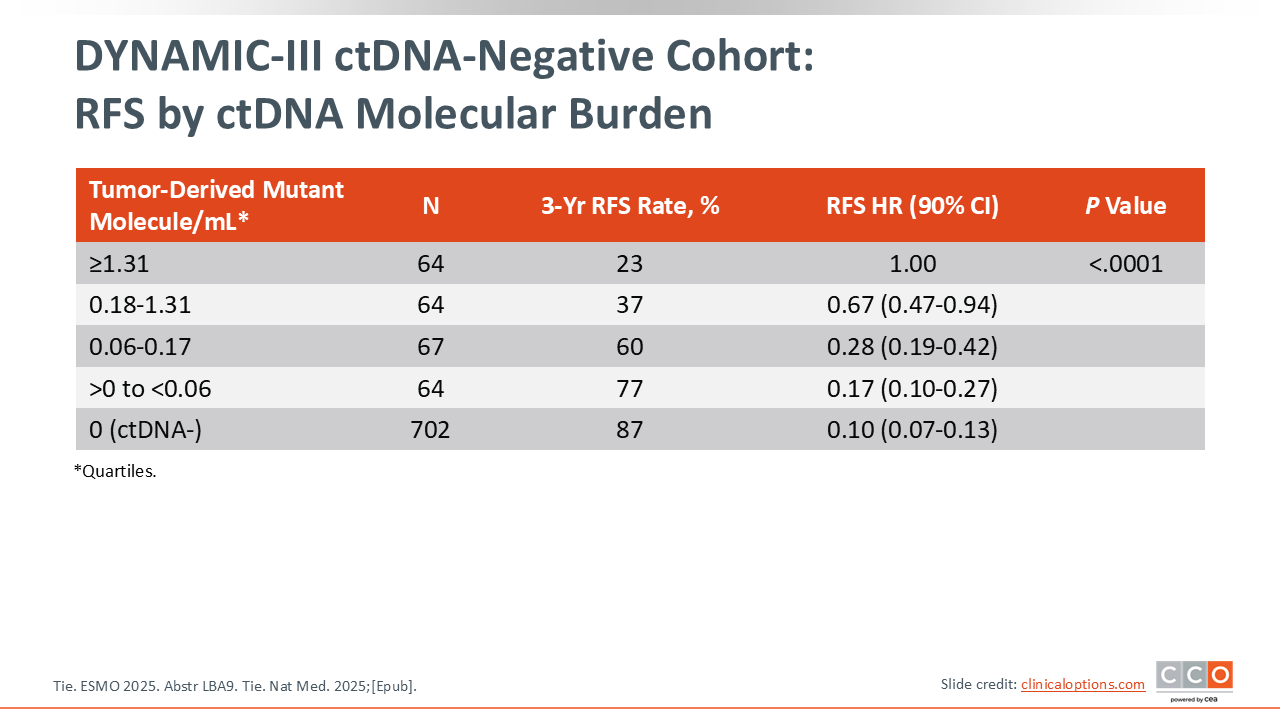

DYNAMIC-III ctDNA-Negative Cohort: RFS by ctDNA Molecular Burden

Zev A. Wainberg, MD:

They also evaluated the prognostic impact of ctDNA, which confirms what we have already known for some time—that it had incredible prognostic impact. However, we cannot conclude noninferiority, and what that means in practice is that it did not change the standard. The standard of care is still to continue with standard adjuvant chemotherapy approaches. This is disappointing, in my opinion, because we had put a lot of hope in ctDNA, not just as being prognostic data, but of more importance, whether it would impact how we treat patients.

Samuel J. Klempner, MD, FASCO:

The quantity of ctDNA being prognostic also makes a fair point about considering ctDNA as part of the staging. This is not my idea, but I think it is a good one. Take stage 2 and 3 colon cancers, for example. If you have a patient with stage 2 colon cancer that is ctDNA‑positive, they may have similar outcomes to a patient with stage 3 colon cancer that is ctDNA‑negative. Technically, those patients are staged differently on the current staging system, but if you added the ctDNA results, it may actually change the outcomes. The whole goal of staging is prognostication. I think in the future, this data set and others will help us to reevaluate the optimal staging criteria in colon cancer. This is applicable to other tumor types as well.

Overall, this was a negative study and not likely to impact routine management of stage 3 colorectal cancers. There are many other ongoing trials that are looking to address variations on this question.

DYNAMIC-III ctDNA-Negative Cohort: Conclusions

Zev A. Wainberg, MD:

At this point, we have to conclude that there is no question that ctDNA is prognostic—that the presence of ctDNA confers a worse prognosis. Essentially, if a patient has ctDNA-positive disease, recurrence is more likely. If the disease is ctDNA-negative, recurrence is less likely. However, there is not much we can do with this information at present. In my opinion, ctDNA continues to be an investigational tool, and in colorectal cancer it should not be regarded as a mechanism by which to alter treatment for patients.

Samuel J. Klempner, MD, FASCO:

There is still an appetite to understand the best ways to deploy ctDNA in colorectal cancer. Certainly, it is very prognostic. In patients with stage 3 colorectal cancer that are completely resected, we do not yet have level 1 evidence to say that this de-escalation approach improves outcomes or does not result in poorer outcomes.